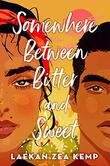

The power of food to bind communities together lies at the heart of Laekan Zea Kemp’s debut YA novel. Somewhere Between Bitter and Sweet (Little, Brown, April 6) features two teenage protagonists struggling with trauma and the expectations of parents and society; they just want to cook together.

Eighteen-year-old Penelope “Pen” Prado has been working at Nacho’s Tacos, her father’s restaurant, for years. Pen wants to craft dishes that bring people together, but her parents have different expectations. After a longtime deception is revealed, Pen is forced out of her parents’ home and restaurant. She has to start over, but all she really wants is to be back where she’s most at home. As Pen is fired, Xander Amaro is hired to work at the restaurant. Xander is an undocumented immigrant who’s spent years searching for the father who abandoned him and his mother. When outside forces threaten Nacho’s Tacos, Pen and Xander come together to face their own demons, cook delicious food, and protect what matters most.

Kemp spoke with us over the phone from her home just outside Austin, Texas. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

It seems like contemporary writers often ignore food in their books. So many characters just don’t seem to need three meals a day.

I’ve noticed this as well. I think you find this problem less in books by people of color and about people of color. For us, food is such a focal point in our lives, and not just for certain holidays or special occasions. For me, personally, it’s how I cap off good days and bad days. It’s how I celebrate, and sometimes it’s how I grieve. Food is my favorite thing in the world! So it was really the most natural thing to show my characters cooking and sharing a meal.

How does food bring these particular characters together?

When the male protagonist, Xander, is walking up to the restaurant for his first day of work, he’s going through the mythology of Nacho’s Tacos and the reputation it has in the community. There are certain dishes that can help with certain ailments, whether that’s physical or emotional or even spiritual. In that way, the food in the book carries a lot of meaning. First and foremost, it’s a symbol of our cultural roots through which we derive so much strength. For anyone who exists in the diaspora, we exist on the peripheries of our culture. We’re not born in our ancestral home, so food is one of the ways we can stay connected to that power source.

For Pen, food is even more important because her identity as a creator is wrapped up in cooking; particularly, cooking in her father’s kitchen. And she believes, really strongly, that is where she belongs and where she’s meant to be—so when he fires her from the family restaurant, she feels completely lost.

Lockdown has changed so many people’s relationships with food and cooking. Has this been true for you?

I think lockdown did create opportunities for me to spend more time digging into dishes—especially those I didn’t feel comfortable attempting on my own before. For example, I made menudo on my own for the first time, which is difficult! We also made tamales for the first time.

For those two dishes it made me realize how much love and labor goes into each one. It occurred to me, as I was spreading masa on the cornhusks and folding them and trying to tie them with string, why it’s the perfect Christmas Eve activity for when everyone is in town. When it was just me and my partner making them together it took us like three days to make four dozen. By the end of it I had the worst crick in my neck!

For those two dishes it made me realize how much love and labor goes into each one. It occurred to me, as I was spreading masa on the cornhusks and folding them and trying to tie them with string, why it’s the perfect Christmas Eve activity for when everyone is in town. When it was just me and my partner making them together it took us like three days to make four dozen. By the end of it I had the worst crick in my neck!

It made me realize for all those things I loved eating—but didn’t always participate in the preparation of—just how much meaning is held in the act of creating them. So the research I did when it came to cooking was incredibly meaningful. It was hard not to get frustrated when recipes weren’t turning out like I wanted them to. For a little while I really struggled not to turn it into some kind of litmus test of my Latinidad. But once I let that go, the whole process was very affirming to me.

You know, I wasn’t born in Mexico; my family has been in the U.S. for four generations. But when I’m in the kitchen, it doesn’t feel so far away. I think that’s such a magical thing to be able to connect with your family history and your ancestral home just by what you choose to put on your plate.

Your website includes some of “Pen’s Recipe Cards.” Are these your own creations?

Some of them are my aunt’s, and some are my grandmother’s, but some are mine.

As a former teacher, do you think about your students while writing?

In terms of the types of stories I tell, my students are always at the forefront of my mind. As an ESL teacher, I spent a lot more time with my students than a regular classroom teacher does. And as their writing teacher, I had the honor of reading about their experiences in their own words. These extremely detailed and vulnerable accounts often left me so moved and speechless.

But at the same time that I’m trying to prepare them for [standardized tests], I’m also constantly coming up against a public school system entrenched in White supremacy. It didn’t take me long to realize the problems I was trying to fix were just too big. There were many times when I left work in tears because I couldn’t protect my students or myself.

The only thing I felt like I could really control was my work outside of the classroom. Working on Somewhere Between Bitter and Sweet sort of felt like the only place where my students and I could be heard without interruption, arguing, or gaslighting. I shouted everything I was feeling in the pages of that book.

You’ve launched a podcast called Author Pep Talks. Who are you hoping to reach?

It’s really geared toward other writers and creatives. I have had times of hyperproductivity during tragedy before. I found through conversations with other authors that those of us who have experienced profound loss, or grief, or trauma were functioning a lot better [during Covid lockdowns] than those for whom this major disruption was new.

I thought in this really unique time when we are all struggling, we might have something to offer. So I reached out to people, and we just chatted about what knowledge and tools past trauma has allowed us to bring into this pandemic.

We talked about things we’re still trying to learn or are struggling with. More than anything, I hope people feel validated in their struggle, but I especially hope writers who are published or pursuing publication are reminded of how nourishing creativity can be.

So far, in every episode, regardless of who I’m in conversation with, it always comes back to Yes, writing is incredibly difficult, especially right now, but it’s also incredibly healing and nourishing. It’s important to remember that.

Richard Z. Santos is the executive director of Austin Bat Cave and the author of a novel, Trust Me.