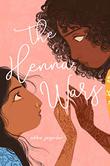

Kirkus’ review describes Adiba Jaigirdar’s debut, The Henna Wars (Page Street, May 12), as “impossible to put down” and with good reason: It’s simultaneously a charming rom-com, a thoughtful work of social commentary, a testament to strong female relationships, and a fresh addition to YA literature. In too many teen novels, queer characters and characters of color—and we still rarely meet queer characters of color—appear in the role of best friend to the straight, white protagonist. Even stories centering characters from marginalized groups frequently focus on their struggles in relation to the dominant culture—as if stories can’t exist without a normative reference point.

Jaigirdar focuses on Nishat, a Bangladeshi Irish teen who comes out as lesbian to her parents, and Flávia, the biracial (black Brazilian/white Irish) girl Nishat is in love—and conflict—with, in a friends-to-enemies-to-lovers storyline. Their connection is founded on a powerful sympathy as queer girls of color in a mostly white Catholic school, yet an entrepreneurial project strikes at the heart of thorny questions of appreciation versus appropriation.

Jaigirdar describes her book as essentially being about “growing into who you are and being comfortable with who you are.” She wrote it, she says, “because of family, community, culture—it was a way to express all of these things that are all so important to me.” Jaigirdar, 26, attended an all-girls’ Catholic school after her family arrived in Ireland from Bangladesh when she was 10. Today, she teaches English as a foreign language to immigrants in Dublin, many of them Brazilian, and she has a 16-year-old sister and young cousins, all of whom helped inform the authentic teenage voices in the story.

Jaigirdar’s M.A. in postcolonial studies motivated her to take on the challenge of writing about cultural appropriation in teen literature. When the girls’ business class teacher assigns them to launch their own businesses, artistic Flávia sees nothing wrong in doing henna designs—after all, she loved the ones she saw at the Bengali wedding where she and Nishat reconnected. For Nishat, on the other hand, henna is a lot more than just something cool and pretty: It’s a deep emotional connection to the grandmother in Bangladesh who taught her how to do it and to her own heritage, which is a source of great comfort but also makes her a target for bullying.

Jaigirdar wanted to explore what cultural appropriation means when the conversation is between two marginalized characters. “I brought this up with a friend who is white,” she explains. “I mentioned that I wanted to write a story about two people of color and that one of them had culturally appropriated from the other. I explained that I thought it would be a very different story than if the other character was white. She reacted very defensively, saying it’s the same thing and it wouldn’t be any different. It inspired me even more to write the story and to think about all of the ways it would be different if it were two people of color.”

Jaigirdar wanted to explore what cultural appropriation means when the conversation is between two marginalized characters. “I brought this up with a friend who is white,” she explains. “I mentioned that I wanted to write a story about two people of color and that one of them had culturally appropriated from the other. I explained that I thought it would be a very different story than if the other character was white. She reacted very defensively, saying it’s the same thing and it wouldn’t be any different. It inspired me even more to write the story and to think about all of the ways it would be different if it were two people of color.”

As a queer Muslim woman living in a predominantly Christian nation, Jaigirdar is also acutely aware of the narrow ways Muslims are often portrayed as well as responses straight Muslims have to different sexualities. Regarding Nishat’s family, Jaigirdar points out that “even though they are Muslim, they are not particularly pious—they don’t pray very often—but you still see them using religion as a reason for their homophobia. I see that a lot within my own community. People who aren’t necessarily religious when it comes to most things will bring out religion and use it for their own motivations.”

Bullying and marginalization in school come up in The Henna Wars as well. Jaigirdar says that “even now, in a lot of schools you would be very hard-pressed to find much diversity, so I think sometimes teachers aren’t aware of how to deal with bullying when it comes to race.” She says she “loved writing about Bengali culture, especially because growing up, I never saw that in books or in the media. When I first started writing the book, I was really just writing it for myself. It was a way for me to see a reflection of myself in books because nobody else had provided that for me. I knew that other Bengali people were also starved for this representation, so I hope that they will resonate with this.”

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.