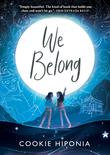

In We Belong (Dial Books, March 30), Cookie Hiponia Everman’s moving debut novel in verse, readers meet Elsie, the mother of two young biracial (Pilipino/White) daughters. They clamor for bedtime stories, and she tells them two intertwined tales. One, springing from Tagalog cosmology, is about Mayari and her siblings, Apolaki and Tala, all children of a mortal woman and a god who ascend to the celestial realm after the death of their mother. The other is about Elsie herself and how she left the Marcos-era Philippines as a child and came to the United States with her family. Elsie’s and Mayari’s stories echo each other, reinforcing themes of loss, longing, and the need to belong. We spoke to Everman via Zoom from her home in the Seattle area. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity

When did you realize that this story was a children’s book?

I was inspired to write this book because of my kids. They’re 12 and 10. For the first six years of my first daughter’s life, I was a full-time stay-at-home mom and hausfrau. [When] I took them to the library, we would always look for books that [they could see themselves in.]. The [Bellevue branch of the King County Library System] is great in that they have a lot of different books in different languages: Tagalog, Vietnamese, Urdu. But they never found a book that they resonated with because they really saw themselves in it. Part of it is because they are hapa—you know, they’re half White and half Pilipino. They felt like the books were either in Tagalog, and so talking about just the Pilipino experience, or they were talking about a [strictly] Pilipino American experience. So I heeded Toni Morrison’s adage: If there’s a book that you want to read, and you haven’t found it yet, then you have to write it yourself.

I knew it had to incorporate mythology in some way. Our younger Pilipino American generation doesn’t know that much about the mythology of the Philippines—all the pre-colonial religious beliefs. I knew that I wanted to explore the mythology but also basically tell the kids our own mythology, our family’s mythology.

I knew it had to incorporate mythology in some way. Our younger Pilipino American generation doesn’t know that much about the mythology of the Philippines—all the pre-colonial religious beliefs. I knew that I wanted to explore the mythology but also basically tell the kids our own mythology, our family’s mythology.

And around the time when I first started writing the book was when we first started having these conversations: “Hey, you know, I was only 9 when I came to the States, just as old as you are. Can you imagine if I told you right now, let’s go, you’re gonna move to a different country, where you kind of know the language but not that well. And you kind of know the culture, but only from TV and movies. And you’re going to be expected to act a certain way and to speak a certain way, and really to look a certain way to belong to this place.” The book grew from there.

I started just writing those conversations down and thinking about the connections between mythology and creating our own mythology as immigrants. It’s tough to move to a different country and be expected to assimilate in a way that asks you to deny a very significant part of who you are. I wanted to preserve that by telling the two narratives at the same time: of the myth and of the immigration story.

The first character readers meet is an adult. How did you find a voice that would be authentic to an adult character and accessible to child readers?

There’s a reason why that old saw about how writers “write what they know” is so true. Elsie is me; I am Elsie. This book is semiautobiographical. I used to work in public relations, and my big joke was, “PR actually stands for perceived reality.” What I was trying to get at with this story is, in all of that perceived reality, what is the truth? And the truth is, this is how I speak to my kids. I don’t sugarcoat anything for them. I might use their vernacular, right? [But] I’m not going to shy away from saying, “Yeah, bad stuff happened to mama.” I always want to speak to my kids with a voice that is true, so I carry that over to Elsie.

I’d like to talk about how you chose the Mayari story and how you researched it.

I’ve always been fascinated with the creation mythology and the celestial siblings mythology, because I’d heard bits and pieces of it growing up: how Mayari and Apolaki fight for the right to be the sun. Apolaki strikes her, and she loses an eye. And I wanted to upend that a little bit, for the fight to be more equal. Bless his little heart, but I’m more fierce than my brother. I brought my own experience of being a middle child into the Mayari, Apolaki, and Tala story, because I was always competing with my brother. I tapped into that: The only way Apolaki could beat Mayari was to take her eye out.

There’s an excellent resource called the Aswang Project. It’s a website [that collects] stories—not just Tagalog mythology, but also all the different regions in the Philippines. They served as my starting point, besides the stories that I heard as a kid. When I was 21, I went to the Philippines on a solo trip, because I needed to reconnect with my roots. I literally came home with a box of books that I [wouldn’t be able to] find here. It was great to really [read in] my old language, my own mother tongue, and relearn those deep Tagalog words, because some of those words were used to tell really old myths.

I didn’t limit my research to just Pilipino references either. I am really fascinated with Anastasia Romanov and her story. What if Anastasia all this time had been living as an orphan in exile? And I thought, OK, what if Mayari and Apolaki and Tala had no idea that they were celestial royalty. I brought aspects of that [into my story].

I took a little editorial privilege. There’s a little bit of daylight here, between this part of the story and that part of the story. What if my story takes place within this little sliver of daylight?

Do you have any last words about your book?

As a person on the margins of so many different groups, I wake up every day with five strikes against me. I’m an older, queer, brown, immigrant woman. So I am very well practiced in finding my own family and figuring out where I belong now. Where you fit in isn’t necessarily where you belong. I can fit in in all kinds of different situations. I can code-switch with the best of them. But I don’t necessarily belong there. And I wanted to tell a story of people who are trying to belong, because immigrants in this country still are trying to belong.

I didn’t come over on a boat. I didn’t come across the border with only the clothes on my back. I had a whole different experience. It was all very bureaucratic. But there still is that universal trauma of leaving somewhere where you’ve felt you belonged and going somewhere else to try to belong there, because this place where you once belonged can no longer keep you safe, can no longer provide the opportunities that you need to survive and to thrive. But what’s the price of leaving that place?

Vicky Smith is a young readers’ editor.