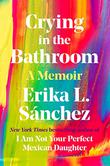

Erika L. Sánchez is one of the hardest-working contemporary Mexican American poets, essayists, and novelists. In the past four years, Sánchez published her debut collection of poetry, Lessons on Expulsion (Graywolf Press, 2017); I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter (Knopf, 2017), a finalist for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature; and this year’s memoir, Crying in the Bathroom, out from Viking on July 12.

These essays reveal a side most of us never learn about a writer’s life. Sánchez divulges “musings, misfortunes, triumphs, disappointments, delights, and resurrections,” taking us on a journey of “salvation in poetry and a life in literature,” according to the Kirkus review.

The following exchange took place via email; it has been edited for length and clarity.

This is your third book, and it follows a similar thematic line as your previous books, focusing on your cultural background as the daughter of immigrants, among many other things. What can readers expect that might be a departure from your previous body of work?

The most straightforward answer is that everything in this third book is true. The themes are similar, but the delivery is very, very different. It’s the hardest book I’ve ever written. Also, it’s a departure from I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, because it’s meant for adults, and the language and content in the memoir are much more explicit. I don’t think I will ever stop writing about what it means to be the child of immigrants because I can’t delete that from my identity or psyche.

In recent years, writers have called for publishers to stop the commodification of trauma and pain of people of color. You write, “I will never pretend that my abortion was easy.” You’ve acknowledged that women of color “are regularly praised for our resilience…it’s a lifestyle that oppression has demanded for us.” Would you say more about this?

I think that is a preposterous notion. You simply can’t police what people write. I dare someone to tell me to my face that I shouldn’t write about trauma. Writing about suffering is not fun; it’s necessary. How silly to even consider asking that from people of color. Writing is how many of us heal. Imagine if someone had told James Baldwin to stop writing about racism. Or homophobia. I don’t even understand the sentiment behind it. We shouldn’t do it because it makes us look bad—so what? I only care about the truth.

Though the memoir is not entirely centered on your misfortunes, they’re an integral part of your story. Similarly, you say that living with mental illness is like “walking a tightrope in heels.” Can you share your experience with depression and the health care system given the heightened awareness of abortion and mental health rights?

In this book, I’m trying to make sense of the misfortunes I’ve experienced. I’m trying to find meaning in things that have hurt me. I wrote about my abortion because it’s not simply a personal matter. It’s an issue that affects women everywhere. Perhaps my words can ease someone’s pain. That’s one of the reasons I write.

In this book, I’m trying to make sense of the misfortunes I’ve experienced. I’m trying to find meaning in things that have hurt me. I wrote about my abortion because it’s not simply a personal matter. It’s an issue that affects women everywhere. Perhaps my words can ease someone’s pain. That’s one of the reasons I write.

If I hadn’t been lucky enough to get mental health care, I don’t know if I’d be alive. But I was privileged because I had a job that provided insurance and could receive treatment. Many people are not so fortunate and have to live with their mental illnesses with virtually no help.

Similarly, women, too, lack access to safe, affordable abortions. I’ve been furious about this since I was a teenager, but it wasn’t until I had an abortion that I truly understood how dire this problem is. We live in a society in which our government venerates guns and fetuses. How, exactly, is that pro-life? I’m so tired of this nonsense. Our health care system is abysmal.

To contextualize your worldview, your book references English and Spanish popular culture, including works of fiction, poetry, religious and philosophical texts, and even television. I was interested in your attention to Buddhism. You say that you have “always been Buddhist.” I don’t consider myself religious, but Catholicism has played a heavy role in my work. How did spiritual practice change or influence your writing?

I also grew up Catholic, and I use a lot of the iconographies. It’s embedded in my DNA, whether I believe in the teachings or not. Buddhism has helped me profoundly because it encourages me to pay attention and appreciate what’s around me. Mindfulness has eased my anxiety and encouraged me to feel boundless and expansive. That translates on the page. I take leaps that I wouldn’t have otherwise.

What didn’t make it into the book that you can share with readers?

There are many things I’ve left out because no one wants to know everything that’s ever happened to me. I’m not that interesting, believe me. I wrote each essay with a theme in mind and built on that. I didn’t write the book chronologically, but that’s how it was ultimately organized. I have many other stories up my sleeve, but I’ll save them for a work of fiction or a memoir in the distant future.

Speaking of future projects, what else are you working on?

There’s an essay I’d like to write about the time I studied abroad in Oaxaca and experienced an unexpected bout of severe depression. There’s a lot of meat in that story, and it’s comical, so it’s been pulling at me. However, I’d like to focus on characters who are not me now that I’ve finished the memoir. I want to get lost in someone else’s world and mind. I’m tired of myself.

Your book follows a line of memoirs that have resonated with me, including Wendy C. Ortiz’s Excavation, Reyna Grande’s The Distance Between Us, and Daisy Hernández’s A Cup of Water Under My Bed, to name a few. I’m always curious to know what other writers are reading. What are you currently reading?

I love The Distance Between Us and A Cup of Water Under My Bed. I haven’t read Excavation yet. I tend to read and teach books by women of color because my students deserve to know about these writers. Many of them had never read texts like that before my class. I’m unabashedly biased. I’m reading The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan, Memphis by Tara Stringfellow, and All the Flowers Kneeling by Paul Tran. I love books with lush language and complicated women and queer characters.

Ruben Quesada is a writer and critic in Chicago.