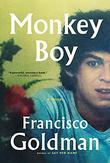

Francisco Goldman’s fifth novel, Monkey Boy (Grove, May 4), plays an ingenious trick. On the surface, the narrative takes place over five days, and yet the narrator—an alter ego of Goldman’s, Francisco Goldberg—detours frequently into his memories, thoughts, and family history, creating the illusion that the reader is immersed in his mind. The result is an intimate and mosaiclike narrative as intricate as the work of Proust or Sebald. Francisco (or Frankie, as he was called growing up) is a novelist and journalist who has recently relocated to New York City from Mexico, where his journalism has gotten him into some trouble. An invitation to dinner by a high school crush brings Frankie back to his hometown, a working-class suburb of Boston that is riddled with ghosts of his past: the cruelty of his peers at school; his abusive father; his own youthful insecurities about being half Jewish American and half Guatemalan. Between trips to visit his elderly mother as well as the Guatemalan women who helped raise him, Frankie pieces together memories that span his entire life, attempting to make sense of the conditions that made him who he is. Goldman spoke to us over Zoom from his home in Mexico City; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re the author of four previous novels and two books of nonfiction. In what ways is Monkey Boy in correspondence with your previous work?

It’s somewhat, superficially, in direct conversation with The Long Night of White Chickens. That was a novel in which the narrator wrote directly about that nuclear family, but I was very young, and my father was very much still alive. It seemed, 30 years later, that it was time to go back and look at the book from an adult perspective. There are references, kind of ironic at times, in this alter ego [Francisco Goldberg] to the course of my writing career. As a writer, I’m completely different now.

Would you say there’s a before and after in your writing, then?

There’s definitely a before and after. I approached the novel [very differently before] my wife, Aura [Estrada], died. That was a very traumatic death and grief experience, which I wrote about in Say Her Name. The [earlier] books were very much concerned with my relationship to the world outside myself, with an eye on political and social realities. I was trying to create a novel that was self-conscious of two novel traditions: Latin American and North American. After Say Her Name, I went inward, and I found myself on a very personal search for how to narrate, a form for the things I needed to address. With Monkey Boy, I feel I’m coming to the end of a cycle again, which began with Say Her Name. These books all have a secret correspondence, revolving around Aura’s death. Aura’s death is the secret presence of this book.

This is definitely a very introspective work. Frankie weaves together many threads of his life, as if he’s trying to make sense of how he became who he is.

In some ways, the fictional root of the book is an examination of how my life would have turned out if I hadn’t met Aura. This came out of preoccupation [and] the guilt you’ll find in Say Her Name, the preoccupation being: Why did it take me so long to find love? And I thought, if I had not had some of the problems I’d had in my upbringing, if I’d been more able to love and receive love as a young man, I probably wouldn’t have ever met Aura and therefore she’d still be alive. And this created a lot of anger in me, toward all the things had malformed me in that way. A completely crazy way of looking at things. But this was the original premise of Monkey Boy.

The book takes place over the course of five days, but a lot of time is covered. We get a sense of Francisco’s entire life in addition to the different histories that formed him.

It was very important for me that this novel really be about moving through time. Frankie is narrating his life as though it is unspooling in his mind. This automatically pulls the narrative away from the realm of realism, because that’s not how minds work. I was creating the illusion of a mind that works this way. But it’s more narrating a sort of bildungsroman that’s running on a parallel narrative track and [is] interwoven with the story of a five-day trip home. I also needed the narrative to read smoothly, as though it wasn’t hard to do even though it was really hard! Ultimately, a five-day trip home isn’t an autobiography; it’s not about what you consider most important in your life; it’s not a grand ambitious statement about a life. So on a five-day trip home to see your mom, what will you think about? You’re going to think about your mom, the town you’re going back to, the girl you knew in high school who’s reached out and just invited you to dinner. But the things that are so weighty in your life get dragged along too. So I wanted to create this dance between the frivolous and the solemn, the painful and the more ephemeral.

It was very important for me that this novel really be about moving through time. Frankie is narrating his life as though it is unspooling in his mind. This automatically pulls the narrative away from the realm of realism, because that’s not how minds work. I was creating the illusion of a mind that works this way. But it’s more narrating a sort of bildungsroman that’s running on a parallel narrative track and [is] interwoven with the story of a five-day trip home. I also needed the narrative to read smoothly, as though it wasn’t hard to do even though it was really hard! Ultimately, a five-day trip home isn’t an autobiography; it’s not about what you consider most important in your life; it’s not a grand ambitious statement about a life. So on a five-day trip home to see your mom, what will you think about? You’re going to think about your mom, the town you’re going back to, the girl you knew in high school who’s reached out and just invited you to dinner. But the things that are so weighty in your life get dragged along too. So I wanted to create this dance between the frivolous and the solemn, the painful and the more ephemeral.

What made fiction the best form for this book, as opposed to, say, memoir?

Well, a memoir is nonfiction, and, because I have had to do some pretty consequential journalism in my life, I know that in nonfiction you can never fictionalize. There’s this absolute, scrupulous fealty to the factual. A novel is autonomous to reality, independent of it.

What was important to me in writing Monkey Boy was not necessarily the kinds of things you would write about in a memoir. The important thing was figuring out how to write this novel. It was that obsession with the illusion of a subject from which, finally, style and structure emerge. Because it’s the structure, the patterns, forms, the way it’s told that finally express what the book is trying to say.

One of the book’s most striking images is a painting of Frankie’s mother, Yolanda, after she married his father. Did this painting actually exist?

When I started writing the novel, I knew the portrait of my mother would be an important image in this book. We always used to tease my mother about that portrait. It was very campy, and we lived in a very modest lower-middle-class household, in a very modest town. So you can imagine how preposterous it was when kids would come over to my house and see this portrait of my mother. Sometimes we were embarrassed; other times we just liked to tease her. I didn’t realize what an important image it was going to be until the book’s patterns of imagery worked themselves out—so by the end of the novel, it becomes a magic portal that allows the narrator to enter her past, which definitely separates this novel from conventional realism.

Roberto Rodriguez is a Poe-Faulkner Fellow in Fiction at the University of Virginia.