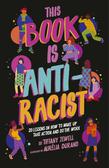

Conversations about race and racism have evolved over years. Like Ibram X. Kendi’s How To Be An Antiracist, Tiffany Jewell’s debut book, This Book Is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on How To Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work (Frances Lincoln, Jan. 7), is an essential tool for any reader hoping to dismantle systemic and internalized bias. This is difficult and oftentimes uncomfortable work, but Jewell has succeeded in breaking down complex concepts, like privilege, complicity, and the dominant culture, into smaller, more easily digestible units. Though the book is geared toward preteens and teens, even adults will find Jewell’s reflections and exercises to be an enlightening and invaluable resource. And the vivid illustrations by Aurélia Durand accompanying the text go a long way to connecting the history of resistance to present-day activism and social change.

Jewell talked about her work as an activist and Montessori educator from her home in Western Massachusetts.

What led you to write This Book Is Anti-Racist?

About adecade ago, while teaching first, second, and third graders at my small Montessori school, I started doing work around the history of racism and anti-racism. Every year the curriculum changed and grew. We used a timeline beginning with slavery and ending with President Barack Obama. The students kept telling me they wanted to learn more, and the curriculum eventually grew to 250 pages. We then began building trust together as a community.

About adecade ago, while teaching first, second, and third graders at my small Montessori school, I started doing work around the history of racism and anti-racism. Every year the curriculum changed and grew. We used a timeline beginning with slavery and ending with President Barack Obama. The students kept telling me they wanted to learn more, and the curriculum eventually grew to 250 pages. We then began building trust together as a community.

Two years ago, I started sharing some of these lessons on Instagram along with Britt Hawthorne, who also does anti-bias education in the Montessori community. Last fall, I received an email from Katy Flint, an editor at Quarto, asking if I’d be interested in writing a book.

Can you talk a little about the exercises in the book?

People always want to know what they can do and how they can do this work. The activities and journal prompts are meant to build personal comprehension. Everyone learns and processes information very differently, but the book gives readers the space to move at their own pace. The lessons allow readers to work at addressing their personal selves so that they can do the work to dismantle racism collectively.

Why are the words we choose to address race and racism so important?

Language shapes power and how we think about things and do things. I wanted the language in the book to be specific. Colonialism took language away from Indigenous people, and there’s such power and ownership when groups reclaim language. Using “folx” with an x, instead of “folks,” comes from black and Indigenous activist circles. The language that you use is your language. You get to own it. It’s how you tell your story.

You use an “imaginary box” to explain the power of the dominant culture—i.e., white, cisgender, heterosexual, able, male, Christian, wealthy, etc. How did this idea come about?

I learned about this idea at a training workshop I attended in Illinois by Crossroads Antiracist Organizing Training. The imaginary box of the dominant culture represents power and influence and helps us to understand who we are and who we are not and how we can change and grow from that. To explain this concept to my young students, I use a physical cardboard box. They understand this. One cisgender boy from an affluent family looked at the box and said, “This is where all the power is.”

Can you talk about your approach of privately “calling in” a person for their bias versus publicly “calling out” someone?

There’s great risk and growth in both.

It’s important to make sure you’re blaming systems, not people. If someone is representing a system, I call them out. Calling out has public accountability and feels safer to me as a woman in the global majority. Some people prefer calling in because it feels safer. If the person is another woman of color, that deserves a call in. I don’t want to call out a woman of color in front of white folks because then they’re justified in all of the stereotypes they’ve compounded on to us.

When I’m called out for something, it requires me to check myself with other people’s eyes on me and then make amends. If we’re going to move forward, it’s really important that we make amends. We don’t have to be friends. But we have to be able to move the movement forward.

Anjali Enjeti is a freelance critic and vice president of membership for the National Book Critics Circle.