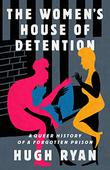

In his 2019 debut, When Brooklyn Was Queer, Hugh Ryan crafted vibrant scenes using details unearthed from quotidian sources like census records and police reports. In his new book, The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison (Bold Type Books, May 10), he uses this talent to cement one building into the history of queer America. The prison, built in 1932 and demolished in 1974, loomed in the heart of Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, next to the red brick courthouse that is now Jefferson Market Library, a few blocks from the Stonewall Inn. Ryan describes the institution’s impact on the queer women and transmasculine people of New York and also surveys the longer history of women’s incarceration, which “is not simply a small mirror held up to the incarceration of men; rather, it is about the development of a distinctly unjust system of justice, violently dedicated to the maintenance and propagation of ‘proper’ femininity.”

When we discuss the book over Zoom, Ryan, a Brooklyn-based historian and educator, the House of D’s influence on Greenwich Village—and queer history writ large—as “an absence that was so present I was shocked.” When asked how he researched, he explains, “Ending up in the historical record is a question of power. You either have power, in which case you can give your objects away to a museum or your house remains and you get a plaque on it.…Or people have power over you, and you enter the historical record as the raw material for their revelations. You enter the historical record because a doctor has studied you, because a social worker has written about you, because a prison needs to keep track of its inmates. The archive is always about power.”

The Women’s Prison Association, an organization for women impacted by incarceration that is featured prominently in the book, allowed Ryan to explore their archives. They were supportive but doubtful that he would find anything relevant, explaining that they didn’t work specifically with queer women, especially not back then. “I opened the files, and within the first day—I think it was in the first two hours of looking—I found one of the most essential stories that I tell in the book,” Ryan says. “And I knew, if I found this file in two hours of looking at 150 boxes, there’s more. And there was.”

The Women’s Prison Association, an organization for women impacted by incarceration that is featured prominently in the book, allowed Ryan to explore their archives. They were supportive but doubtful that he would find anything relevant, explaining that they didn’t work specifically with queer women, especially not back then. “I opened the files, and within the first day—I think it was in the first two hours of looking—I found one of the most essential stories that I tell in the book,” Ryan says. “And I knew, if I found this file in two hours of looking at 150 boxes, there’s more. And there was.”

Each chapter of The Women’s House of Detention brings to life those who entered the historical record under duress. We meet people erased from history as well as figures who feature prominently in it, including former inmates Andrea Dworkin, Afeni Shakur, and Angela Davis. Toward the end of the book, Ryan writes, “For every story told in this book, there are fifty I didn’t tell—and a hundred I never found.” I ask him to share one of those stories and am gifted with a yarn about a 6-foot-tall woman from the Midwest whose only childhood friend was an eccentric millionaire. She moved to New York City and had an affair with an opera diva, ending up in jail after their breakup sparked a breakdown. She later killed a man while serving as a playground guard.

“It stuck with me,” Ryan explains, “how easy it could be for someone to live a life in this moment of possibility that they seem to jump into and embrace. But because they are poor and because they have so few family or government or community supports, that when one bad thing happens—a gonorrhea diagnosis that is actually not a gonorrhea diagnosis or this break with her lover and she has nowhere to go so she’s left on the streets—it can just fuck your life up forever. It can knock you entirely out of the slim, fragile bubble of queer possibility that you found and guarantee you a life of trying to be heterosexual, or at least invisible.…I’ve felt a little bit of guilt for finding her story and not telling it. She was owed something. Or somebody. It makes me sad.” Here, Ryan audibly chokes up and wipes tears from his eyes.

Some pushed back on Ryan when he pitched this project, advising him to focus on something more “relevant” first. “And I just had this sense that queer history, and this generation of queer history…was so poorly captured at the time, so poorly historicized, so deeply repressed, that that work is critical to do right now, and to not just pass around the same six memes about Stonewall.” Of the living people he spoke to about their experiences in the House of D, all but one have since died.

I ask Ryan what he wants people to leave this book with. He gives me—you, us—two challenges: “That the prison system is irredeemable and needs to be fundamentally destroyed or transformed. And that queer history is fragile, and all of us have a place in saving it.”

Kyle Lukoff’s most recent book is Different Kinds of Fruit.