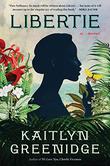

History infuses Kaitlyn Greenidge’s fiction—but she turns school-textbook history on its head to reveal its underside. Her first novel, We Love You, Charlie Freeman (2016), about an African American family raising a chimpanzee and teaching it sign language, was deeply informed by the history of racist medical experimentation in the United States. Her enthralling new novel, Libertie (Algonquin, March 30), opens in a free Black community in Brooklyn in the years before the Civil War; it follows the titular character—the daughter of an esteemed female doctor—to college in Ohio during Reconstruction and ultimately to a marriage in Haiti. Kirkus’ reviewer praised the book, saying, “Greenidge shows us aspects of history we seldom see in contemporary fiction.” I spoke with the author by Zoom in Massachusetts, where she has been living during the pandemic. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I understand that the original inspiration for the novel came from a museum you worked at years ago.

Yes. That museum, the Weeksville Heritage Center, is dedicated to preserving the history of Weeksville, a free Black community founded in central Brooklyn in 1838. People originally founded it to have a concentration of Black voters in New York state. Before the Civil War, to be able to vote in New York you had to own a certain amount of property, so after Black people were freed, they wanted to strategically buy up as much property as they could to make sure that they could have a Black voting bloc and determine their own destiny. Then, of course, once you had that space, it became a place of refuge for people escaping slavery and for abolitionists looking for places to safely organize.

The museum itself was founded in 1968, when residents in the neighborhood rediscovered all of this 19th-century history and wanted to save the buildings that had been standing since the 1830s. New York City was [engaged in] urban renewal and destroying basically all those buildings to build housing projects. It is a space with extraordinary energy and extraordinary history that is often counter to the dominant narrative around Black working-class people in this country. All of that was super fascinating to me, and I wanted to write about it.

There was a woman doctor in Weeksville who was the model for Libertie’s mother in the book?

Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward. Her father, Sylvanus Smith, was one of the founders of Weeksville, and she grew up there and was the first Black female doctor in New York state. She went on to found a hospital for women and children in the neighborhood, and she was a patron of many different charities and schools, all Black run and founded. Her story is interesting, but it’s a standard in Black history. We often focus on these exceptional histories—the first black person to do X. And I was more interested in the emotional toll of that sort of exceptionalism for a person and for a person’s family. I also wanted to talk about the people who are not driven to do that. The main character of the novel, Libertie, is the daughter of the first Black female doctor in New York state, and her ambitions don’t lie there. In fact, she really questions the whole system that her mother is buying into by fighting to be the first. I wanted to write about that tension within narratives around Black history.

Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward. Her father, Sylvanus Smith, was one of the founders of Weeksville, and she grew up there and was the first Black female doctor in New York state. She went on to found a hospital for women and children in the neighborhood, and she was a patron of many different charities and schools, all Black run and founded. Her story is interesting, but it’s a standard in Black history. We often focus on these exceptional histories—the first black person to do X. And I was more interested in the emotional toll of that sort of exceptionalism for a person and for a person’s family. I also wanted to talk about the people who are not driven to do that. The main character of the novel, Libertie, is the daughter of the first Black female doctor in New York state, and her ambitions don’t lie there. In fact, she really questions the whole system that her mother is buying into by fighting to be the first. I wanted to write about that tension within narratives around Black history.

Unlike so many books that are set during the period around the Civil War, where the conflict would be center stage, here it’s almost happening offstage. The war is dispatched in a few pages, really. That was an interesting choice.

So many novels have been written about the Civil War, and it’s difficult to write about it without falling back into cliché. I wanted to get at the feeling of rage that I think is oftentimes erased from recollections of Black people’s experiences around the Civil War. And to get to the rage, I had to really focus on Libertie’s actual, lived experience. One of the things that is often overlooked in the romance of this war—of brother against brother and men on the proving ground—is the lives of people who did not fit those roles, who were still living and organizing and keeping the world going while this other grand thing was happening. We are currently living in extraordinary historical times, and I’m always struck by the counternarratives that are continually happening underneath this grander story about how we’re all experiencing it in a particular way.

This novel has one of my all-time favorite opening lines: “I saw my mother raise a man from the dead. ‘It still didn’t help him much, my love,’ she told me.”

Early on in the drafting process, I wrote a nonfiction article about an abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor named Henrietta Duterte. She was a Black woman in Philadelphia; her husband was Haitian. He owned a funeral parlor; she owned a dress shop. The funeral parlor was a stop on the Underground Railroad, and they used coffins to help people escape. So that imagery was in my mind right away. I knew that I wanted part of the story to be this romance between Libertie and her mother, the doctor and her daughter, and the things that happen between seeing your parent as superhuman, as your hero, to that developmental thing that we all go through when you realize that your parent is human—just another flawed person like you are. I was trying to find a way to convey to a reader both Libertie’s childish belief in her mother’s superpowers—and also how that wasn’t real.

You mention your nonfiction article, and you do write a lot of articles and op-eds. Does fiction let you approach some of these same topics from a different angle?

Fiction is a chance to be expansive with my imagination. It’s not necessarily tied down to citations or to sources or anything like that. You can just follow where your imagination naturally goes. There’s a freedom in fiction that is not necessarily there in writing nonfiction.

There’s a question that Libertie—and the reader—keeps coming back to throughout the novel: What is freedom?

I was reading a lot of theories about romantic love and romantic attraction, trying to figure out how I was going to set up this romance between Libertie and Emanuel [the Haitian man who works as an assistant to Libertie’s mother]. And I was really struck by a Toni Morrison quote, where she says that in Western culture we don’t necessarily have an understanding of love that isn’t built around domination; we don’t have an understanding of freedom that isn’t built around domination. We don’t have definitions for freedom that aren’t about being able to get away with transgressions against people that are weaker than you. And that’s simply how U.S. citizens define freedom for ourselves. What would freedom mean to you, as a dark-skinned Black woman in the 1870s, knowing that everybody else is measuring their freedom by what they can get away with doing to you? And that became sort of the driving question for the book.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.