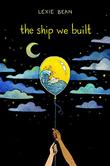

In Lexie Bean’s debut middle-grade novel, The Ship We Built (Dial, May 26), readers meet Rowan Beck, a 10-year-old trans boy in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in the late 1990s. Rowan hardly speaks, but he writes letter after letter, sending them aloft via helium balloon to no known recipient. These letters and his friendship with classmate Sofie sustain him through his fifth grade year, as he endures both ostracism at school (he’s blurted out his true identity as a boy) and nighttime visits from his father at home. In their author’s note, Bean writes, “This book is a gift to my ten-year-old self. I was nine when I stopped speaking at school. I was ten when I wrote my first suicide note.” We talked with Bean from New York via Zoom; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

This book defies so many rules associated with middle-grade novels. You really focus the plot on Rowan’s interiority and day-to-day existence, with no added drama.

A lot of that [is because I was] writing for a past version of myself. And I think what I needed at that time wasn’t a grand mystery or a plot that will keep me turning the pages—what I needed was a friend. I’m a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, and I think days can just feel so long and every thought feels small and stupid when [you’re] growing up in an abusive environment. I wanted to stay true to life and its slowness and how out of control it feels sometimes. I also think the imagination steps in when you’re not busy. And his imagination is what keeps him alive to a great degree.

Even though Rowan is writing so much, some things are hardly spoken—the abuse that Rowan endures is so understated.

He doesn’t have the vocabulary, and even if he did, he might not be ready to name it. Abuse is such an isolating experience, so I didn’t want him to find the words for what’s happening, partially because I didn’t. I wanted readers to understand what [abuse] does to someone’s relationship with their voice. I think if it wasn’t for the abuse, he wouldn’t have written the letters to begin with. If he were only navigating gender, it would have been a completely different story.

He doesn’t have the vocabulary, and even if he did, he might not be ready to name it. Abuse is such an isolating experience, so I didn’t want him to find the words for what’s happening, partially because I didn’t. I wanted readers to understand what [abuse] does to someone’s relationship with their voice. I think if it wasn’t for the abuse, he wouldn’t have written the letters to begin with. If he were only navigating gender, it would have been a completely different story.

This was probably one of the hardest parts about how [abuse] has impacted my own gender journey. Because one of the doubts [Rowan] has throughout the entire book is wanting and not wanting to be a boy, because he’s being hurt by one. I haven’t seen that represented anywhere. And I think it’s really important to talk about, especially considering that trans boys have the highest suicide rate in the LGBTQIA umbrella. But I didn’t want to center it because I think survivors shouldn’t be expected to talk about their abuse all the time in order for it to be real. It’s a part of Rowan’s everyday life. And so he’s going to talk about it like it’s his everyday life, and that includes not talking about it all the time.

I also wanted to be honest about the feeling that there’s no good place to go. And I think regardless of abuse, a lot of queer or trans youth feel like school’s not good, home’s not good.

At this moment when kids are literally trapped in their homes, this might be an even more valuable book than you imagined when you started.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot. In the synopsis it never says the word trans or queer or even sexual abuse, and I’m really grateful for that. I chose not to include those words because those words just wouldn’t be part of [Rowan’s] vocabulary. But now, people who have those experiences but wouldn’t necessarily be in an environment where their parents would get them a trans book, or a book that deals with these topics, could still hypothetically get [it] because the words aren’t on there.

One of the things that struck me about your author’s note is that you say this book is probably going to be banned.

Yeah, if they don’t complain about the queer parts, they’re going to complain about the abuse parts. A lot of people might [say it’s not] child appropriate. And I guess my response to that is: As long as children are experiencing it, it is child appropriate.

Vicky Smith is a young readers’ editor.