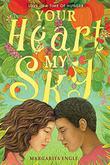

Your Heart, My Sky: Love in a Time of Hunger (Atheneum, March 23) is a work of historical fiction in verse from international-award-winning Cuban American poet Margarita Engle. In Cuba during the summer of 1991, Liana, 14, and Amado, 15, choose to stay home rather than go to work in the government’s farm labor program. They risk serious consequences: Amado’s brother is already in prison for avoiding military duty. Listless from hunger in a country where malnutrition is rampant, they nevertheless fall in love after their paths cross. Liana is accompanied by Paz, a stray singing dog she adopted, one lone survivor of an ancient breed known for its haunting vocalizations, who becomes the third narrator in the novel. As the situation in Cuba becomes more dire—something thrown into relief by the arrival in distant Havana of athletes for the Pan American Games and the increasing numbers of people fleeing by raft for Florida—Liana and Amado debate what to do: stay and try to make the best of things, even through illegal means, or attempt to cross the sea themselves? Engle spoke with us over Zoom from her home in Clovis, California; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Your author’s note describes how you visited Cuba during this time. Why write about it now?

I have been thinking about it for a long time; I wrote about this hunger while it was happening, for adults. I tried to get people in the U.S. to care—and, frankly, adults often didn’t believe me. A lot of people would argue with me. Many people still believe myths: They either demonize or idealize Cuba instead of seeing it as a real place with real people. My reason for starting to work on this particular version of the hunger of the ’90s as a love story came from hearing people reminisce about it during more recent trips to Cuba. The summer of 1991 was when I was finally able to return, after a 31-year absence, due to travel restrictions. As Cuba lost Soviet subsidies, the economy was in free fall, they were desperate for hard currency, and they let non–Eastern bloc travelers in for the first time during the Pan American Games. It was illegal for my relatives to talk to me—the Cuban people had been instructed not to speak to foreigners—so I visited them in secret. It was a very surrealistic experience, seeing their hunger. Food had been rationed since the ’60s. People who imagine paradise and equity don’t understand the complexity of the situation.

I have been thinking about it for a long time; I wrote about this hunger while it was happening, for adults. I tried to get people in the U.S. to care—and, frankly, adults often didn’t believe me. A lot of people would argue with me. Many people still believe myths: They either demonize or idealize Cuba instead of seeing it as a real place with real people. My reason for starting to work on this particular version of the hunger of the ’90s as a love story came from hearing people reminisce about it during more recent trips to Cuba. The summer of 1991 was when I was finally able to return, after a 31-year absence, due to travel restrictions. As Cuba lost Soviet subsidies, the economy was in free fall, they were desperate for hard currency, and they let non–Eastern bloc travelers in for the first time during the Pan American Games. It was illegal for my relatives to talk to me—the Cuban people had been instructed not to speak to foreigners—so I visited them in secret. It was a very surrealistic experience, seeing their hunger. Food had been rationed since the ’60s. People who imagine paradise and equity don’t understand the complexity of the situation.

My hopes are that young readers will be compassionate and empathetic. I want to say that I love the cousins who stayed—and I love the cousins who left on rafts. I want to be free to see Cuba as a real place rather than an idealized or demonized place. I want family unity. I want normal diplomatic relations, which four years ago we seemed to be headed into, which would have helped to ease hunger. I feel like it’s important, even so many years later, for people in the U.S. to understand why the rafters left and that that situation could be reversed: People could be leaving the U.S. on rafts. If there’s ever a year when we can believe that anything can happen, it’s now—and that’s why we need compassion.

I was fascinated to learn about the singing dogs—wouldn’t it be wonderful if some of them really had survived! How did Paz come to have a voice in the novel?

Singing dogs were the indigenous dogs in the time of the Taínos, and the Spanish priests who went with the conquistadores wrote about the dogs who sing instead of barking. The voice of the dog was a way to portray history. During the time of hunger in the ’90s, cats and dogs were very hard to feed—people didn’t have extra food for pets. So, for there to be this dog in a story that the teenagers want so badly, for me that was a reminder of hope. I wanted to have these two young people not be alone. Also, it represents the senses that are used for survival—the dog helps them find food by tracking. When we really need food, people turn to their very basic instincts. None of us can say, Oh, no, I wouldn’t buy illegal food. I wouldn’t just swallow things out of the ocean without knowing what they are. Yes, you would.

On top of the starvation, there is pain that comes from the divisions that harsh government policies created between people. Liana and Amado face ordinary teenage relationship difficulties as well as life-or-death questions around trust and risk.

Whenever you have a national government that’s authoritarian, there’s censorship, silencing, fear, and distrust, even within families. The government wanted to keep track of every single movement by every single person. There are neighborhood committees to report [on] this. It’s something that I hadn’t wanted to write about a lot because I’m seeking unity—and yet, it’s part of reality. The people who left on rafts left for both reasons, for food and for freedom of expression.

You’ve been writing for young readers for some time. Do you have any thoughts about where we are now with young people’s literature?

I think there are some wonderful trends. I love the way verse novels have been accepted. I love the success of so many poets—Kwame Alexander, Jacqueline Woodson, Jason Reynolds—so many people have skyrocketed to fame and popularity, and nobody says anymore, Oh, kids don't like poetry. The Poet Slave of Cuba [Engle’s verse biography of Juan Francisco Manzano] was published in 2006, but verse novels were kind of a poor stepchild of the publishing industry.

When I was named Young People’s Poet Laureate in 2017, people would walk up to me and say, I don’t like poetry. Now you’re this evangelist for poetry, don’t make me read it. These were adults; that’s not what the kids were doing. The kids like an uncrowded page; that’s inviting. Teenagers write poetry. A wonderful thing that I learned going to schools was that if I read a poem, they’d pull one out of their pocket and read one to me, too. And they weren’t writing it because I was there, they were writing poetry anyway. Seeing the young poet [Amanda Gorman] at the Super Bowl? These kinds of things wouldn’t have been likely to happen 10 or 15 years ago.

I love the way translations are being offered by the publishers: Most of my newer books are published either in simultaneous translations or a year later at the most. I felt like [before] if you walked into a bookstore, the only books in Spanish were translations of English bestsellers written by non-Latino people, whereas now most Latinx authors can get our books in both languages, and that means so much for family literacy. That’s fantastic, that a child and a grandparent could read the same book, each in the language they’re most comfortable with, and discuss it.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.