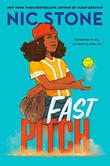

Children’s and young adult writer Nic Stone has hit the mark again with her new middle-grade novel, Fast Pitch (Crown, Aug. 31). Following Stone’s 2020 novel, Clean Getaway, Fast Pitch tells the story of Shenice “Lightning” Lockwood’s race to win the championship for her fast-pitch softball league while being drawn to solve a family mystery that was uncovered in the middle of the season. The book combines frank, age-appropriate discussions of racism with positive representations and a loving family dynamic. Stone spoke with Kirkus by phone from her home in Atlanta, Georgia, about her experience of researching the Negro Leagues for the story, explaining racism to tweens, and the need for positive representation in children’s and young adult literature. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Having grown up with Black parents who were in a healthy, loving relationship, I really appreciated the characters of the parents because I don’t think we see enough of this in literature. Can you tell me a little bit about the inspiration for this?

Honestly, this part just came out of real life and wanting the story to be focused on this girl trying to shoot her shot and chase after this thing that she really, really cared a lot about. So, without the baggage of a single-parent home—not that single-parent homes are bad—there’s something beautiful about having supportive parents and being able to chase this dream that she had. Her parents are kind of loosely based on my husband and I. It was important for me to have her come from a solid family base.

You recently posted to Instagram about your joy upon seeing the cover illustration.

The interesting thing about the cover is that I didn’t see it until it was almost done. When I did, I just started sobbing because she does look just like me. People are actually under the impression that the cover was drawn based on me, and it wasn’t. The artist just did a really good job of portraying the person I described in the book. I cried like a baby because it was my first time ever seeing a person who looked like me, and was doing something that I would do, on the cover of a book. It was the fact that I get to be the person to put that out in the world. I don’t take that for granted.

The interesting thing about the cover is that I didn’t see it until it was almost done. When I did, I just started sobbing because she does look just like me. People are actually under the impression that the cover was drawn based on me, and it wasn’t. The artist just did a really good job of portraying the person I described in the book. I cried like a baby because it was my first time ever seeing a person who looked like me, and was doing something that I would do, on the cover of a book. It was the fact that I get to be the person to put that out in the world. I don’t take that for granted.

When I saw the cover, I knew that I was going to have to do a cosplay of the cover with myself in the same clothes that she was wearing. So, the photograph in the jacket copy [and above] is me, literally in the same pose as Shenice, with the softball hovering over my hand.

There’s a scene in the book where the players show up to a town, and Shenice and her teammates notice that there are Confederate flags all over the other teams’ cars. It reminded me of my own experience of moving to the South and realizing that, yes, these people do exist in the world.

I live in Georgia, but I live in Atlanta, which is basically a blue oasis politically and otherwise, but if you go even 30 miles outside of the city, you’re in an entirely different place. If I were to drive my family to the panhandle of Florida, there are certain cities we drive through on the way there that you see Confederate flags. I wouldn’t stop for gas in certain places.

I think it was important for Shenice to have to reckon with the feeling. I know when a lot of kids have firsthand experience with racism, they just don’t really know what to do or how to feel because it just feels weird. You feel a way, but you’re not sure of how to put it into words. She and the whole team have to reckon with what they were seeing, with these White coaches talking them through it and also struggling with it a little bit.

It was important for me to put it in the book because as much as it’s a book about softball and a book about winning a championship, she also in that moment gets to identify a little bit with what her great-grandpa might have been feeling.

Great-Grampy JonJon, who was a player in the Negro Leagues. Can you tell me about the experience of researching that history?

There is a part in the book where [Shenice] talks about the stress of not being able to find something on the internet. I literally pulled that from what I was feeling when I was trying to do all this research to find out more about the Negro Leagues and trying to find rosters for the Negro Leagues, and none of this stuff really [got] recorded. I couldn’t find anything on the internet, and it was kind of stressful because it made me think about how much history we just don’t know about because it wasn’t recorded. That was an interesting experience, and it’s made me more cognizant of things going on around me and the fact that there are things that I will never know about because they weren’t written down. It’s a really humbling thing.

Let’s talk about writing about racism for a tween audience.

Talking about racism, no matter who you’re talking to, there’s no way to make it palatable. There’s no way to talk about racism in a way that isn’t going to jar the person you’re talking to, especially if the person is a kid. When I am talking to kids about race and racism, the most important thing to me is making sure that after any discussion, I leave them feeling empowered. It’s really imperative to make sure that children know that, yes, this is how things were, and even how things are, but you’re still a human being with agency.

I am really excited for this generation of children because they will have literature that is more representative than we had growing up.

Absolutely. For my kids, there’s no lack of books with them in them and on them, which is a beautiful, beautiful thing. And I just hope that the numbers increase and increase, because it’s not just for us. Books about Black kids are not only for Black kids. They need to be read by everyone. Everybody needs to see Black kids thriving, Black kids saving the day and solving mysteries. These are really important things for other people to see. It’s been quite an honor to be able to put some of the stuff out into the world.

Your novel is a nice departure from the theme of the child who is escaping a bad situation. I really appreciated that while I was reading.

There are more than enough of those. There are more than enough stories about Black kids who are struggling. Black kids dealing with racism. Black kids trying to get out of the ’hood. I’ve written those stories, and, oddly enough, those are the stories that sell the best of all the stories that I’ve written. It is also important to see a kid’s No. 1 conflict be I really want to help my team win the championship, but I got to figure out this stuff with my family.

What are you working on right now?

What I can say is that there will be three YA releases next year. I don’t have any middle grade. My next middle grade will be in 2023.

Nia Norris is a journalist in Chicago who writes about culture and social issues for Ms., Romper, and Next City.