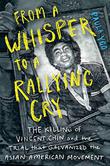

From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial That Galvanized the Asian American Movement (Norton Young Readers, April 20) is Paula Yoo’s gripping account, written for a young adult audience, of the tragic 1982 death of a young Chinese American man beaten by a White auto worker in Detroit at a time when tensions over Japanese car imports were running high. Chin’s killer, Ronald Ebens, served no time, receiving only a nominal fine and parole for manslaughter. Following a grand jury indictment, Ebens was found guilty of having violated Chin’s civil rights but was acquitted upon appeal. The case led to nationwide protests, heightened awareness of racism faced by Asian Americans, and the growth of a pan–Asian American identity and community, yet it’s a story that has lapsed into obscurity. The escalation in anti-Asian hate crimes in recent years makes this an especially critical read.

Yoo is a former journalist (at the Detroit News and other publications)–turned–screenwriter and producer (she worked on TV shows such as The West Wing and Supergirl). She brings her considerable experience to the book, which balances a dynamic narrative with exemplary research, including interviews with many of the people directly involved. Yoo spoke with us over Zoom from her home in Los Angeles, California; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

As you worked on the book, did your impressions of the problem of anti-Asian racism change?

We have always been excluded and erased from the dialogue about racism in this country. Vincent Chin’s case was the first federal civil rights trial for an Asian American, and this was the 1980s. My friends and I joke occasionally about [how] being Asian American is like dying by a thousand cuts, a thousand microaggressions. But I’m realizing now that’s also part of the conversation: Unfortunately, most Americans think of racism in very broad strokes, as wearing a KKK hood or [going] up to someone, [punching] them in the face, and [calling] them a racist slur. Obviously, there’s a higher priority for violent physical crime, but that does not erase the importance and complexities of microaggressions. Trauma happens, whether it’s one shocking, horrifying event or a lifetime of tiny microaggressions that add up. What I am happy about, though, is that we’re finally having this conversation and finally addressing all forms and varying degrees of racism. You cannot have one conversation about racist mass shootings and not have an equally important conversation about microaggressions. For the Asian American and Pacific Islander experience, that is what we know, and the rest of the world is now finally finding out. So I would say my one surprise is that it took me this long to have this conversation.

Like many Asian Americans, I have long held the impression that there was unambiguous, incontrovertible evidence that this was a hate crime and that the lax sentencing reflected the ongoing struggles we’ve had as a community to get society to take anti-Asian racism seriously. I finished reading your book surprised at all the complex, complicating factors at play: conflicting eyewitness testimony, other forms of bias that affected the course of the police investigation, problems with how manslaughter cases were routinely handled in Michigan, issues with the prosecution’s gathering of evidence, and more. I emerged with a greater understanding of how the aftermath unfolded the way it did as well as feeling like I had a full enough picture of events to draw my own conclusions.

I was a little frustrated at first because I wanted it to be cut and dried: There is an evil villain and then you’ve got your superhero. But that wasn’t the case at all—both men had flaws, there was toxic masculinity on both sides, everyone had been drinking too much. Legally speaking, it was also complicated because at the end of the day, Ronald Ebens was found not guilty of violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights. Is he guilty of manslaughter? Yes, he pled guilty. He knew what he did was wrong. To this day he still expresses remorse. He still insists that he is not racist. Because Ebens was ultimately found not guilty in the 1987 second trial for violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights, he and his legal team believe this also means his actions were not the result of racism but of a bar brawl that turned tragic—and fatal. The complication is, what exactly is your definition of racist? The complexity at first daunted me. I thought, what can I really say about racism? He was found not guilty.

I was a little frustrated at first because I wanted it to be cut and dried: There is an evil villain and then you’ve got your superhero. But that wasn’t the case at all—both men had flaws, there was toxic masculinity on both sides, everyone had been drinking too much. Legally speaking, it was also complicated because at the end of the day, Ronald Ebens was found not guilty of violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights. Is he guilty of manslaughter? Yes, he pled guilty. He knew what he did was wrong. To this day he still expresses remorse. He still insists that he is not racist. Because Ebens was ultimately found not guilty in the 1987 second trial for violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights, he and his legal team believe this also means his actions were not the result of racism but of a bar brawl that turned tragic—and fatal. The complication is, what exactly is your definition of racist? The complexity at first daunted me. I thought, what can I really say about racism? He was found not guilty.

But then, the more I delved into it, the more I realized that it’s a complicated case because racism is a complicated topic. If it was good versus evil, if it was simply him wearing something obvious like white Ku Klux Klan [robes] and if there was an actual smartphone back in 1982 that recorded him saying [racist] words, sure, that would be an easy story to tell. But would it be as effective? I think it is important and vital that the case was as complicated as it was because that shows the difficulty of how racism is perceived in this country. The rise in anti-Asian racism because of the pandemic [has] been bringing up difficult conversations as well about anti-Blackness and other types of prejudices within our own communities. There are things we have to address right now about our own flaws, but I hope this book also reminds people that there also have been many bridges that were built, decades ago, that are very strong, and we’re walking across those bridges.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope my book has a positive impact on young readers in terms of showing them that they have a voice, that their lives, their history, and their heritage matter. I hope my book has a positive impact on young readers who may not be Asian, [that] it will inspire them to learn more about the contributions we’ve made in this country and to form not just allyships with other communities, but friendships. Because one of the most important things about this book is that the activists were not just Asian, they were White, there were Jewish organizations, Black organizations, the Latino community, Pacific Islanders—everybody joined in together. I hope that people walk away from this not only feeling anger and wanting to do something, but also proud of how people of many different backgrounds can actually get together and work toward a common good. We have to fight hate with love. We can also fight with anger, but our anger is fueled by that love. My heart breaks thinking about what kids are going through right now because of this traumatic pandemic, and I hope that this book gives them hope—to know that no matter how dark things get, you can always find the light.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.