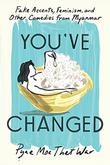

As a creative writing student in the United States and England, Pyae Moe Thet War struggled with how much of her Myanmar heritage to include in her work. “I wanted my voice to be funny, and unflinching, and thoughtful; I didn’t believe that my voice could be all of those things as well as being Myanmar,” she writes in her new essay collection, You’ve Changed: Fake Accents, Feminism, and Other Comedies From Myanmar (Catapult, May 3). Now, as a writer who has come into her own, War’s voice is all of those things and more, tackling topics that range from home and belonging to baking and loss in a debut that our starred review calls “a delight to read.” War spoke with Kirkus via Zoom from her home in Yangon, Myanmar; the interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In each essay, you describe aspects of Myanmar culture, but you never fall into a mode that feels too explanatory. You stay focused on your personal narrative. How did you strike that balance?

I’ve always said that I write for myself, and this is the advice I give to younger writers. When you’re a younger writer, you get into your head about who your audience will be. I would have panic attacks where I’d worry, What if this subset of readers doesn’t agree with this part? For a White American audience, do I need more exposition? Am I being disingenuous if I write like this even though that’s not how I would talk? I decided to approach these topics as if I were talking with a close friend. [In an actual conversation with a friend] at some points, I would say, “Go Google this yourself, this isn’t relevant to this story.” I had to tune out the idea of a target reader and think, How would I tell this story? and stay true to that.

Your essays have such witty beginnings and endings. What is your writing process like?

The writing process is very disjointed. I always write in chunks. Then I go back and restructure these chunks while thinking about how they connect. For “Tongue Twisters,” the essay on accents, I distinctly remember brushing my teeth one night when two paragraphs popped into my head. I ended up texting a friend, “Damnit, now I have to open my laptop again.” Other times, I write with an ending in mind, but then I have to figure out the beginning and middle. You’re not always ready to write everything you want to write. The accent essay I wanted to write for years. I’d bring it up in conversations with friends, but I wasn’t ready to write it. That essay took the most research. Eventually, I got to a point in my career where I finally felt like I could do it justice.

The writing process is very disjointed. I always write in chunks. Then I go back and restructure these chunks while thinking about how they connect. For “Tongue Twisters,” the essay on accents, I distinctly remember brushing my teeth one night when two paragraphs popped into my head. I ended up texting a friend, “Damnit, now I have to open my laptop again.” Other times, I write with an ending in mind, but then I have to figure out the beginning and middle. You’re not always ready to write everything you want to write. The accent essay I wanted to write for years. I’d bring it up in conversations with friends, but I wasn’t ready to write it. That essay took the most research. Eventually, I got to a point in my career where I finally felt like I could do it justice.

How do you approach research? You pull from so many sources, from the TV show Key & Peele to historical journalism to academic texts.

I owe a lot of my research skills to when I was an undergrad and I’d write academic papers all the time. When I’m working on an essay, I’m consumed by it. I’m always keeping an ear out in case I hear a reference on TV or someone sends me a story, and I’ll make a note of it. It’s very chaotic. I’ll have 50 tabs open [on my web browser] and think, But I can’t close any of them! I might need them! I love research. I didn’t think I would, because when I had to write papers in college, I’d say, Once I’m an adult I’m never going to do research again, I’m never going to cite an article again.

There were parts of You’ve Changed that took me by surprise, especially when I was expecting a happy or tidy ending. I’m thinking of “Paperwork,” your essay on the bureaucracy of immigration.

I wrote that essay thinking it would be wrapped up in a neat, little bow. I didn’t think it would be the most difficult essay to edit. I would cry over it, saying to myself, Oh my god, you’re so naïve. It originally ended at the section break before its current ending—[my life changed] as I was editing it. When I added the new ending, my editor asked me, “Are you comfortable with this?” Even though we’re writing for the public, writers need to have healthy boundaries. But when I’m committed to talking about a certain topic, I owe it to the reader to be as honest as possible. The old ending would have felt like lying because I know how this ends. I know it doesn’t end happily, nicely, or beautifully. To let the reader think otherwise would be disingenuous.

The essay does end beautifully. There is so much power in your voice. When did you know you were confident enough in your voice to carry a full essay collection?

Especially as a writer of color, you’re always wondering, Oh, am I being arrogant? For me, as a young, brown woman, [as my book approaches publication] I’m still like, Oh my god, who do I think I am that I could write an entire essay collection? But at some point, you’ve just got to go for it. It was important for me to write the book that I wanted to write. It would have been worse for me if I had written the book in a voice that wasn’t truly my own or was something that other people wanted from me. Even if other people had said, “This is a great book,” I would have known that it wasn’t honest. As a writer, not everybody in the [publishing] industry is going to be rallying around you. You have to make sure that you’re pushing for your stories.

Along the lines of what others might want from you, have you ever felt pushed to write about Myanmar from a foreign policy point of view?

When I was freelancing and doing some journalism, I never felt knowledgeable enough to write along those lines. There is this expectation, You’re Myanmar, you should know everything about Myanmar, but would you go up to someone in the U.S. and ask them, “Do you know everything about American history and foreign policy?” For young, brown writers, for Myanmar writers, your boundaries are so important, especially when there’s that temptation to just want your name out there. When you’re from a marginalized and underrepresented community, it can be so hard to say no, because you wonder if you’re shutting a door forever, but at the end of the day, you’re the one whose name is going to be on a piece.

And as a writer, you can’t be everything to everyone. Who are some other Myanmar writers you’d like readers to check out?

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint’s memoir Names for Light is so beautiful. I reference MiMi Aye’s cookbook Mandalay a lot. I don’t really cook, but it’s one of the few cookbooks that I own. Charmaine Craig, who wrote Miss Burma, has a new novel [My Nemesis] coming out [slated for February 2023]. I wish there were more names I could name. I can’t wait for a lot of Myanmar names to be dominating Publishers Marketplace deals.

Hannah Bae is a Korean American writer, journalist, and illustrator and winner of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award.