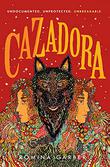

Romina Garber’s Wolves of No World series combines Argentine folklore with topical issues of immigration, identity, and the gender binary. Its main character, Manu, is an undocumented immigrant from Argentina who lives in the United States with her mother, terrified of being discovered and deported. Manu eventually discovers she is also the first known lobizona—a female werewolf—and that her mother has been hiding her from a secret magic underworld because being a lobizona is illegal in the Septimus system, a world with a rigid gender divide. Upon discovering her status, Manu embarks on a journey of self-discovery that reaches a pinnacle in the second book in the series, Cazadora (Wednesday Books, Aug. 17), which sees Manu and her friends fighting for freedom and equality. Garber spoke to me about the books via Zoom from her home in Miami. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Like your main character, Manu, you are from Argentina, based in the United States. Can you talk a bit about this confluence in your work?

A lot of the inspiration and the motivation for getting this book out had to do with what happened in 2017 at the United States border under the previous administration. It brought to mind a lot of the stuff my parents had told me about how they met in Argentina at the end of la Guerra Sucia [Dirty War], a violent military overthrow in the early ’80s, and how dissidents who spoke up against the junta disappeared—which is a pretty way of saying they were murdered. No one knows what happened to them to this day.

A lot of the inspiration and the motivation for getting this book out had to do with what happened in 2017 at the United States border under the previous administration. It brought to mind a lot of the stuff my parents had told me about how they met in Argentina at the end of la Guerra Sucia [Dirty War], a violent military overthrow in the early ’80s, and how dissidents who spoke up against the junta disappeared—which is a pretty way of saying they were murdered. No one knows what happened to them to this day.

Then I started seeing reports about families being separated at the U.S. border and children being caged. It made me think a lot about my parents’ story and the idea of wanting to raise your children with more hope and more potential for the future. You try to escape darkness, and yet the notion that borders could even stop dangers like those is silly, because they’re born from ideas, and ideas cannot be contained by borders, walls, or documents. I had it in my head nonstop, this idea of history repeating itself.

You also pay homage to Argentine folktales and culture.

I decided to incorporate wolves and witches because it’s part of Argentine lore through this whimsical law that is still in effect today, which states that the president becomes godparent to the seventh consecutive son or daughter in a family, and the state covers their educational expenses until they are 21 years old. There is a superstition at the heart of this that states that the seventh son is a lobizón, and then there are some versions that talk about the seventh daughter being a bruja [witch]. I found that so fascinating, because it speaks to the way that language and words and narratives can really concretize into laws—and even sometimes cages.

These different experiences from Argentina really came together to show how that line between fantasy and reality can sometimes be as thin as the page you are turning. And this law ties into the immigrant story as well, as it supposedly came over from Russia, because there were some diplomats in Argentina in the early 1900s and they had this tradition back home. So really the superstition stems from Russia, and then it became adopted in South America. It just speaks to globalization and the idea that everything affects everything, and none of us are really isolated in any way.

There’s a lot of straddling between fantasy and the real world with the story’s focus on the gender divide. Girls like Manu are expected to be witches, never lobizonas.

We live in factions: divided in houses, in neighbourhoods, in countries. We are bound by binary thinking and the gender rigidity of this world. The Septimus system is very much taken from the machismo that is so prevalent in South American countries, and I’m particularly focusing on Argentina and the outrage I’ve felt with so many cases of femicidio—women being murdered and men getting off scot-free. There’s this cultural expectation of this is what it is to be a man, and this is what it is to be a woman, and it’s so toxic. I really wanted to dismantle that.

Let’s talk about magical realism in your books—the inevitable question for any Latin American author working with fantasy.

I wouldn’t call it magical realism because there is a system in it, and usually there are no real rules in magical realism. I’m sure there’s an argument to be made, especially in the beginning of the book, for magical realism—until you figure out what is going on, and then it’s very hard to continue to hold that up. You bring up such a good point because sometimes people like to throw words at your work, like tropes, such as the magical school and the chosen one, but I really believe that until everybody has had a chance to try it, you really can’t call it a trope. If a brown undocumented girl hasn’t been the chosen one, then it’s not a trope yet. I feel the same way about this—just because I wrote a contemporary fantasy that involves an all-Latinx cast doesn’t mean it should be labeled magical realism.

Speaking of labels: Manu gets labeled many things in her story.

I am a writer. I’m an adorer of words. But I understand words could never define me or describe me or contain me, and I’m afraid that we are getting to such a point where we are so reductive—everything needs to be labeled. That translates into the bigger issue of systems and the notion that we shouldn’t have to modify ourselves to fit into systems, but rather systems should be modified to fit us. We should be reexamining laws because the world of today didn’t exist yesterday, and all of these things really tie together into the idea that we need to examine our language. We need to examine it, because it is the building block of civilization. I almost see this series as a treatise on labels.

I understand the books were originally planned as a duology, but Book 2 has a very open ending.

It’s not really an ending, it’s the setup for a new beginning. I always saw Manu’s story concluding in a courtroom battle as an undocumented immigrant. But then, you know, it wasn’t an ending at all: This is a sentencing and a new beginning.

Ana Grilo is co-editor of the Hugo Award–winning blog The Book Smugglers and co-host of the Fangirl Happy Hour podcast.