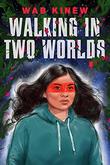

With Walking in Two Worlds (Penguin Teen, Sept. 14), Wab Kinew, the leader of the Manitoba New Democratic Party, draws upon his personal and family history as well as his Anishinaabe heritage and activism (he was a witness for Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Kinew previously published a memoir, The Reason You Walk (2015), and a nonfiction picture book, Go Show the World (2018). In his gripping new teen science-fiction title, he introduces readers to Bagonegiizhigok “Bugz” Holiday, an Anishinaabe teen who has a massive following in the virtual reality gaming world of the Floraverse, where she stands up to her online rivals Clan:LESS, a group of misogynistic White supremacist boys whose unsubtle, militaristic approach to gameplay contrasts with Bugz’ elegance. In real life, however, Bugz wrestles with body shaming and social anxiety. When Feng, a Floraverse gaming rival and the Uyghur nephew of the reservation’s new doctor, shows up at her school, the teens’ parallel worlds collide. Kinew spoke with us over Zoom from his home in Winnipeg; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to write for teens?

The genesis for the book was a few trips that I took to a boarding school for First Nations kids in northern Ontario called Pelican Falls. I noticed that many of the young people there were reading YA fantasy. Talking to [them] about the challenges that they faced—moving away from home, trying to pursue education, mental health, and relationships with peers—really got me thinking over this refrain that we hear a lot in the Indigenous community about walking in two worlds. For somebody growing up today, it’s not just the two worlds of Indigenous and mainstream. It’s the worlds of virtual and real—and for a young person, the virtual world is at least as important as the real world.

The video game sequences and the social dynamics of the gaming world were riveting and so well realized.

My kids are avid gamers. When they were younger I’d watch them play Minecraft, and that proved to be fertile soil for the more creative side of the Floraverse. Watching them play with their friends online was really the inspiration for how much interactivity and culture-building there is in online communities. I was [also] a gamer growing up. The abusive talk, the trolling, the pack mentality? Unfortunately, I did witness that. Being more of the Nintendo generation rather than the PS5 generation, growing up my whole life hearing that video games are bad for you, I did want to have that balance in the book where I highlight some of the positives. This is just a part of reality for young people today, and we should be confident that as long as we’re helping them to reach their full potential, they’re going to turn out all right—even with these influences that we don’t always understand as the older generation.

Witnessing how Bugz lovingly builds a world in the Floraverse based on Anishinaabe cultural elements she treasures is so powerful. And it stands in real contrast to the more destructive approach of Clan:LESS.

As great as our technology is, it’s only as good as what we put into it. Coming from an Indigenous perspective, where we’ve often been left out of the mainstream conversation, I wanted to flag that there’s a danger in ignoring the Indigenous perspective once again as we move into an AI–powered future. I hope that a young Indigenous reader may feel reassured that they can be who they are in this tech-powered future, and I would hope that the non-Indigenous reader would just nod their heads and be like, Well, yeah, of course, that [perspective] should be part of it, along with all the other influences that are out there.

It’s fascinating to meet Uyghur characters and witness how they settle into the Anishinaabe community and examine their own experiences as members of a marginalized, persecuted group.

In spite of whatever barriers are put between people—social or political—if you put two kids in a room together, they’re going to talk to each other and learn about each other. The reality most of us live in is that many people have mixed backgrounds, mixed ancestries; these relationships happen all the time, even if they’re not well documented or celebrated. I think that the situation Uyghurs are facing in Xinjiang now is one of the great human rights travesties of our time. Not only do I think it’s important to weigh in on that, I also think it’s important to encourage young people to have a global perspective. Part of encouraging young people to spread their wings fully is for them to understand they’re citizens of the globe—and part of that can be finding shared challenges. There’s a scene in the book where they’re exchanging parallels between the [Uyghur] detention camps and [First Nations] residential schools. Other times it’s more positive, like some of the cultural exchange that happens around the Indigenous sweat lodge or at the dinner table in the Uyghur family’s household. Not only are you part of a global community online, you’re part of the global community in the real world.

In spite of whatever barriers are put between people—social or political—if you put two kids in a room together, they’re going to talk to each other and learn about each other. The reality most of us live in is that many people have mixed backgrounds, mixed ancestries; these relationships happen all the time, even if they’re not well documented or celebrated. I think that the situation Uyghurs are facing in Xinjiang now is one of the great human rights travesties of our time. Not only do I think it’s important to weigh in on that, I also think it’s important to encourage young people to have a global perspective. Part of encouraging young people to spread their wings fully is for them to understand they’re citizens of the globe—and part of that can be finding shared challenges. There’s a scene in the book where they’re exchanging parallels between the [Uyghur] detention camps and [First Nations] residential schools. Other times it’s more positive, like some of the cultural exchange that happens around the Indigenous sweat lodge or at the dinner table in the Uyghur family’s household. Not only are you part of a global community online, you’re part of the global community in the real world.

Within marginalized communities, there’s often a tension between the drive for cultural preservation in the face of mainstream cultural dominance and the reality that living cultures are not static and that long-term survival comes from younger generations engaging and changing things. You develop this theme so thoughtfully.

I think this is a major piece for young people from all backgrounds, but I’ve witnessed it up close in the Indigenous community. Often it is [about] gender, as it is in the book. LGBT youth face situations like this, where a young person who’s very keen and gung-ho to participate in the traditional culture may be made to feel like an outsider or feel shame in some way that I think is not right. Many of the challenges that Indigenous youth face were created by being forcibly removed from their culture. Often the solutions come from encouraging young Indigenous people to participate in their cultures again—but if those are not safe spaces, then the young person needs to know that it’s OK to prioritize their safety or well-being. There is some balance between how much we just carry on the legacy that we’ve inherited versus how we respond to what’s going on around us and add our own piece to it. I hope to encourage young people to know that you can participate in a traditional way of life while also standing up for yourself or what you think is right. Dogma is not good wherever it comes from; it’s better if we can engage with things, and talk about them, and process them, and then try the path that we want to walk for ourselves.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.