Biography is perhaps the trickiest of the literary arts. In addition to possessing dogged reporting and research skills, the biographer must also be a shrewd psychologist, getting inside the mind of the subject and understanding their motivations. This involves a lot of evidence-gathering along with, inevitably, some highly educated guesswork.

“Biography is not merely a mode of historical enquiry. It is an act of imaginative faith,” writes Richard Holmes in This Long Pursuit: Reflections of a Romantic Biographer (Pantheon, 2017), a collection of essays on his chosen craft. Holmes, who has written biographies of of Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Samuel Taylor Coleridge among others, likens biography to “a handshake across time,” emphasizing the deeply personal nature of the work.

Jenn Shapland, the author of My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Tin House, Feb. 4), knows just how intimate biographical work can get. As she explains to Kirkus in an interview on p. 62, while doing archival research on McCullers, she came across the novelist’s letters to Swiss photographer Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach; she recognized them instantly as love letters, though most McCullers scholars have obscured the author’s lesbian attachments and focused on her two marriages to Reeves McCullers. The discovery led Shapland to a deeper recognition of her own queerness, along with her subject’s, and the book she ultimately wrote is a self-aware hybrid of memoir and biographical meditation.

Jenn Shapland, the author of My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Tin House, Feb. 4), knows just how intimate biographical work can get. As she explains to Kirkus in an interview on p. 62, while doing archival research on McCullers, she came across the novelist’s letters to Swiss photographer Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach; she recognized them instantly as love letters, though most McCullers scholars have obscured the author’s lesbian attachments and focused on her two marriages to Reeves McCullers. The discovery led Shapland to a deeper recognition of her own queerness, along with her subject’s, and the book she ultimately wrote is a self-aware hybrid of memoir and biographical meditation.

Biographers have been popping up in their own work ever since Edmund Morris somewhat notoriously made himself a character—and a fictional character, at that—in Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan (Random House, 1999). In the preface to her recent memoir, Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simon de Beauvoir, and Me (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2019), Elaine Bair writes, with a note of distaste, that “contemporary biographers who find little or no information about their subjects feel scant compunction about inserting themselves into lives which they played no part, either as authoritative characters or commentators.” Bair didn’t inject herself into her biographies of Beckett and Beauvoir per se, but Parisian Lives is a vivid, standalone recollection of her encounters with these two literary titans and a glimpse at Bair’s own progress as a scholar. Would-be biographers can learn a lot from it.

Biographers have been popping up in their own work ever since Edmund Morris somewhat notoriously made himself a character—and a fictional character, at that—in Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan (Random House, 1999). In the preface to her recent memoir, Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simon de Beauvoir, and Me (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2019), Elaine Bair writes, with a note of distaste, that “contemporary biographers who find little or no information about their subjects feel scant compunction about inserting themselves into lives which they played no part, either as authoritative characters or commentators.” Bair didn’t inject herself into her biographies of Beckett and Beauvoir per se, but Parisian Lives is a vivid, standalone recollection of her encounters with these two literary titans and a glimpse at Bair’s own progress as a scholar. Would-be biographers can learn a lot from it.

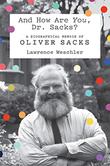

In the 1980s, New Yorker staff writer Lawrence Weschler set out to write a series of profiles of the author Oliver Sacks (Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) for the magazine, meeting with his subject over the course of four years. Sacks, who was gay, was uncomfortable coming out so publicly, and the profiles were killed. Last year, four years after his subject’s death, Weschler published And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?: A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). Note that “biographical memoir” in the subtitle—this is no straightforward, cradle-to-grave account of Sacks’ life , but rathwr a recollection of the author’s onetime subject who became a friend and godfather to his daughter. Weschler, in an interview with Kirkus last year, called himself a “beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote.”

In the 1980s, New Yorker staff writer Lawrence Weschler set out to write a series of profiles of the author Oliver Sacks (Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) for the magazine, meeting with his subject over the course of four years. Sacks, who was gay, was uncomfortable coming out so publicly, and the profiles were killed. Last year, four years after his subject’s death, Weschler published And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?: A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). Note that “biographical memoir” in the subtitle—this is no straightforward, cradle-to-grave account of Sacks’ life , but rathwr a recollection of the author’s onetime subject who became a friend and godfather to his daughter. Weschler, in an interview with Kirkus last year, called himself a “beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote.”

We live in a word with fewer boundaries—and greater transparency—than ever before, and our books reflect it. These complex hybrids of biography and memoir, when done scrupulously and honestly, can make for rich reading.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.