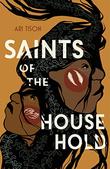

Saints of the Household (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, March 28) by Ari Tison is a bold, innovative debut and a love letter to her BriBri heritage. It follows Indigenous Costa Rican brothers Jay and Max, who are growing up in Minnesota under the burden of their White father’s violence. Jay’s chapters are narrated in powerful prose vignettes; Max’s are told in evocative verse. BriBri stories are interspersed, adding even more richness to the novel. When the book opens, the brothers face disciplinary action and mandated counseling for assaulting their cousin Nicole’s boyfriend after he threatened her. Jay and Max cope very differently with conflicting demands: protecting their mother from their father’s assaults, juggling school commitments, planning for life after high school, and wrestling with inner fears about their own behavior and their father’s legacy. These differences strain the boys’ relationship at a time when they need each other more than ever. Tison spoke with us over Zoom from her home in rural Wisconsin; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you choose to write for teens?

The voices just came as teenagers, though I’ve had plenty of adults read the book and feel like they saw themselves. [For] a lot of us who are trauma survivors, YA books can be healing; there’s a lot of meaning to the genre because of its ability to do that. I think the world of YA and what it can do.

Can you talk more about healing and what you hope readers will take away?

One of the things I set out to do with this book was to recognize that healing after trauma takes a long time, and sometimes stuff shows up when you think you’re safe. The boys experience something really hard in the middle of the book, and what comes after all that is not easy: There’s trauma and PTSD and situational depression and all these things that now we have to work through? I thought I just got through this! But it’s the truth, right? It’s just the way it is. For young people to know that is good. As a teenager, I wish I had known that things are not easy, but there are resources—community, art, faith, kinship—to guide us along the way. And that’s my hope for the reader.

Grandpa Fernando is such a wonderful presence, a grounding, caring figure who connects the boys to their BriBri culture, stories, and language. Was this relationship inspired by your own life?

My dad passed last year, but we used to talk for hours about why we loved being Indigenous: We know the stories of our places, our locations. There are stories behind everything, and so you can’t help but love and care and want to protect [them]; you have this connection. The butterflies have a story, the rocks have a story, the mountain does—the mark on the mountain does.

My dad passed last year, but we used to talk for hours about why we loved being Indigenous: We know the stories of our places, our locations. There are stories behind everything, and so you can’t help but love and care and want to protect [them]; you have this connection. The butterflies have a story, the rocks have a story, the mountain does—the mark on the mountain does.

My dad was orphaned at a young age, and he ended up on a student visa in a Mennonite community in Ohio—a wild transition! I grew up without BriBri grandparents. I’ve got BriBri aunts and uncles still living that I adore and love to learn from, but as a child I didn’t have access to my elders in that way. For this book it was beautiful to start thinking, what would that space have looked like? It’s wishful but also healing, a lovely little capsule of wisdom and perspective.

I am incredibly proud of the ways that we have protected our language: Most BriBris speak BriBri, which is wild considering colonization. It’s a privilege as a Native nation to be able to speak our language; it gives me a lot of hope. We’re just starting to bring back our naming, which is really quite a beautiful thing.

What are your thoughts on writing for an audience that mostly will not be familiar with BriBri culture?

There’s only five of us that live here, so I joke: If I sell more than five books, most of my audience [will be] non-BriBri people. There’s a lot of grace that we give up front, and we’re willing to share: My mentor [Mainor Ortiz] is super giving. He got here a couple of years ago, and the first thing he did was teach a community class on BriBri culture, literature, and language. I took my dad and my brother, so there were 4 out of 5 BriBris there, but there were other people there too—it wasn’t just us, and I think about that when I write. Of course, there’s Indigenous knowledge that I don’t share, things that I know that are secret. With the stories [in the book that have] never been translated into English before, that’s a gift to the reader but also, in turn, it's a way for me to document things for future BriBris in the U.S. and people who might not have access to Spanish and BriBri as well. I get excited thinking, my son’s going be able to read it; that means something to me. So I’ve done the work of thinking about my people but also thinking about my reader. I hope both can exist, but it was a weird space to be in at the beginning: Who’s going to even read this? But then I was reminded, Ari, you’ve read books that have nothing to do with your people, and they’ve influenced you and grown you and shaped you. So why couldn’t stories about BriBris do that, too?

Max’s paintings play such a pivotal role in his character’s arc, and the power of his voice, presented in poetry, adds so much to the novel. I understand you write poetry and paint as well.

My husband introduced me to painting, and that really got me thinking because I was pushing myself in a different art form. Painting is a lot more abstract, and I think it mirrors poetry in that way. I always get jazzed about hybridity, but I always want to make sure that it serves the book. That was really a compelling part about Max, that he had an art form that I was new to. I loved getting to listen to the Tate Museum’s archives of artists talking about their work—they sounded like poets! So it was really fun to capture Max’s rhetoric: What is art causing him to think about?

I was intrigued by the centering of boys’ voices in a story that explores, among other things, the impact of violence against women.

I think as a creative writer, I needed some distance from my characters in order to enter into the story. But just like any work of fiction, the cool thing is that we get to try to put on the mind of somebody else. It made me think about community, what happens when different abuses rub up against each other, and our BriBri stories about our own survival and our own monsters. I didn’t switch genders purposefully, but I think it brought out a lot of nuances that I had to explore.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.